The Road to Perfectly Broken

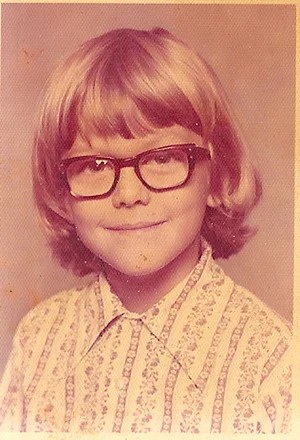

I arrive in the year of Rubber Soul, Highway 61 Revisited, and My Generation: 1965. My Journalism major mom and guitar-playing Marine dad divorce before I turn two. Mom retains custody of my elder brother, Britt, and me. We come of age in Atlanta, in the waning days of the hippie dream and the onset of disco; arts festivals, backwoods, communes, the golden age of Top 40 radio, and a house stocked with books and LPs.

My father dies driving drunk a couple weeks after my seventh birthday. Mom returns to school to study medicine. Maternal grandmother, Gammie, steps in to help raise my brother and me. Her husband, my grandfather, Sam F. Lucchese, is the retired entertainment editor of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and a stringer for Variety. He still taps furiously on a manual typewriter in the basement of their home, the percussive clickety-clack-BING rising from below while we watch All in the Family and the Carol Burnett Show. My writing gene comes from the Lucchese line.

I pen stories and poems and co-edit a newspaper for teens, but in those early days, Dad’s musician genes hold sway, and I focus most of my energy on music. I pick up a bass at fourteen and devote myself to it. Within a couple years, I start a band with my longtime best friend, guitarist Todd Butler. Our singer is superstar-in-exile RuPaul. We call ourselves Wee Wee Pole. We write and perform Prince-inspired material. From Gammie’s kitchen, I book us a tour to Manhattan. I am eighteen.

We pull in to NYC at dusk, RuPaul driving the van. I am wide-eyed. I adore everything about the city. The gigs go great, but I soon quit Wee Wee Pole and accept an invitation to move to Athens, Ga. to join arty rock quartet Go Van Go, peers of my favorite band, REM. A room in an antebellum house awaits me, along with an opportunity to find out who I am away from everything I know.

After half-heartedly attending classes at University of Georgia, playing in Go Van Go for a year (including another tour to NYC), and writing lots of letters, I pull up stakes and head north to take a stab at New Yorker-hood. With my bass and $500 made from selling Christmas trees in the winter of 1984, I arrive with no clear plan other than join a band. I am nineteen.

I don’t know it at the time, but I am among the last wave of artists to be able to live cheaply in Manhattan. I get lucky and find a $600-a-month tenement sublet on Ave. B in the East Village. I join a succession of groups, playing stages ranging from CBGB to the Palladium. To pay my bills, I make Xeroxes at the Village Copier and wash glasses and tend bar at King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut. King Tut’s becomes a kind of gender-bending Cheers family for me.

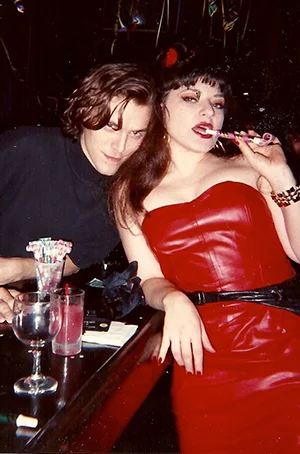

In autumn of 1986, I join globetrotting garage rock titans the Fleshtones. They’ve already been at it for ten years. They need a bassist, and when they see me play at Wigstock ’86, we hit it off. The band is finishing up their newest album, Fleshtones vs. Reality, and domestic and European tours are imminent. Thus begins a rock n’ roll odyssey through France, Italy, Spain, Greece, Martinique, Germany, Switzerland, and all over the U.S. “college circuit.” We share stages with James Brown, Chuck Berry, John Hiatt, NRBQ, Sir Ian McKellen (!!), and many others. I am a working musician. The first year with the Fleshtones is one of the happiest of my life. I’m twenty-one.

In the midst of the adventure, I meet my wife, fellow dreamer Holly George, a writer and rocker in her own right. I settle in to her St. Mark’s Place apartment and compose lots of songs. When I’m on the road, I compose lots of letters. By late 1988, I am tired of being a Fleshtone and want to do my own thing, so I quit the band. Holly quits her editing job at American Baby magazine, and we get married, beginning the next chapters of our lives together. She yearns to write music biographies, I yearn to be a rock star, or at least a working artist. I’m twenty-four.

The early 90s are a fitful time for me. I bounce from band to band, act in black box theater plays and independent short films, compose and demo countless songs, and write letters. I return to tending bar to help make the rent. When I’m invited to join a band called Pleasurehead in 1991, I think my ship has come in. They’ve nabbed a deal with Island Records, label of Bob Marley and a little band called U2. Pleasurehead (later renamed Crush) features the former drummer of Killing Joke and former guitarist of Siouxsie and the Banshees. We sound like a cross between Led Zeppelin and Jane’s Addiction. With INXS producer Mark Opitz at the helm, I record an album with them at the Jimi Hendrix-designed Electric Lady Studios on West 8th. (That record will never be released.) Despite all of the above, extreme personality conflicts are too much for me, and I quit. (Island soon drops them.) I join the band of former Jesus and Mary Chain member John Moore, but within a year, I leave that situation, too. I return to the bars, and woodshed intensely as a songwriter, burning through several cassette four-track recorders. I work on my guitar playing, book solo acoustic gigs, and accept the occasional “money gig” as a bassist. I’m twenty-seven.

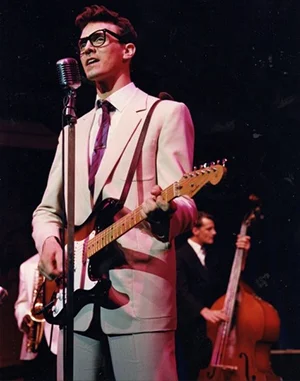

In 1994, I land the lead in the long-running West End/UK production of jukebox musical Buddy: The Buddy Holly Story. They need a slim, tall, guitar player-actor-singer, and that’s me. I move to the UK for a year – I live mostly in London – to act and perform seventeen songs a night, five nights a week, in a three-hour production. The show is a huge hit, selling out sizable venues, and I perform for more people in a year than I have in my entire life. I turn thirty in the dressing room of the Victoria Palace Theatre, one of the biggest houses in London.

Upon returning home, I keep auditioning and get some OK gigs, but the urge to do my own work intensifies while my confidence as a creator fades. Unbeknownst to me, Holly sends a cassette of mine to Rosanne Cash, who is auditing songs for her 1995 Essence of Songwriting workshop at the Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, NY. Rosanne likes my material and invites me to join the workshop. This changes my life. I gain some confidence and begin to find my voice. I return to Essence of Songwriting in ’96 and ’97. It is very much like summer camp. Rosanne and I become friends. She invites me to help her and husband-producer John Leventhal finish the song“44 Stories”. It ends up on her Grammy-nominated album Rules of Travel. She and I correspond frequently via email, and she not only encourages my songwriting, she enthusiastically advises me to write prose.

In early 1998, Holly’s and my son, Jack, arrives. While Holly works in Midtown as editor of Rolling Stone Press (Wenner Media’s book division) I take care of Jack in the East Village. This experience is another seismic event, about which more later. Suffice to say, at this juncture, I am thirty-two.

At night, I record my rootsy-yet-funky debut CD, … to this day, which I self-release in 2000. It does very well, garnering raves in Billboard, Mojo, and the New York Times. It’s the featured album on NPR’s World Café. One of my songs gets placed in the TV series Felicity. I play the occasional gig and sell out a small pressing via the Internet and at shows. But mostly I look after Jack, a job I love more than anything. Much of the time I am deeply happy to be where I am, doing what I’m doing. I feel a sense of purpose unlike any I’ve ever felt. I am rarely bored. Parenting is a challenge in many ways, but in that challenge comes a sense of kinship, not only with fellow parents in Tompkins Square Park, but all parents. I notice the ways in which parenting changes relationships and world views. These themes will eventually emerge in my writing.

In 2001, we have a terrible year. We lose the St. Mark’s apartment through a legal battle, Holly’s parents both pass away (dad, expected, mom, unexpected), Wenner Media closes its book division, and from our rooftop, we watch in horror as the Trade Towers fall. I’m thirty-six.

We move to the Hudson Valley in 2002. Holly closes her first deal to write a biography: Public Cowboy No. 1, The Life and Times of Gene Autry. We buy a house and put down roots, enrolling Jack in preschool at School of the New Moon. I take a job as a teacher’s assistant at that preschool, and when Jack heads to kindergarten, I stay on at SNM for four years. During this time I learn a lot about early childhood development, and the changing dynamics of families. I also chop a lot of wood for my boss and write epic progress reports about every student.

My boss encourages me to bring in my guitar, and soon I’ve made up a bunch of songs and recorded them in our spare bedroom with seven-year-old Jack on background vocals. I call myself Uncle Rock. Over the next five years, I release several CDs, all of which do well. I earn a decent wage as a children’s music performer. The scene into which I cast my lot is dubbed “kindie.” I have a lot of fun, touring and recording with great musicians, and garnering significant airplay on satellite radio. Jack and I perform together a lot, and that is the best part of it all. I’m forty.

While making music for kids during the day, I begin to write in earnest at night, taking on journalism gigs, cranking out musician bios and liner notes, and ghost writing. I read more than I ever have, which is saying something. As a gift for Jack’s 10th birthday, I create a book featuring characters he and I have made up at bedtime. The book is a YA fantasy entitled Yelloweye, and it gets me an agent. This agent shepherds me through a rewrite, after which we part ways. I spend the next couple of years writing Angel Blues, a YA novel about an 80s hair metal star and his estranged son. These books are the greatest marshaling yet of my creative energy.

After hurricane Irene devastates our Catskills neighborhood in 2011 (we get off relatively easy), I sit down to write a novel about fictional people I could possibly know. I’ve been circling around this task for years, but something about the wanton destruction wrought by Nature emboldens me to finally try. By now, of course, I’ve seen much go down in my family and in my peer group, and I realize the universality of many of the bullet points: the respective fallout of dreams fulfilled or unfulfilled; longtime relationships cracking and/or strengthening under the weight of age and grief; pharmaceuticals changing interpersonal dynamics; damaged adults fearing they’ll repeat their parents’ mistakes; infidelity and other betrayals; the adventure that is parenthood; kids altering relationships; unquenchable erotic attraction; heroism and forgiveness; unexplained magic.

While taking on various money gigs, I spend three and a half years weaving all of the above and more into a novel entitled Perfectly Broken. Lou Aronica, president of publishing house The Story Plant, loves my book and publishes it in March of 2016. I’m fifty.

More to come. Thanks for reading.

RBW, 2016